Confidential OSINT Report: Afghanistan as a Terrorist Safe Haven Post‑U.S. Withdrawal

1. Executive Summary

Since the U.S. military withdrawal in August 2021, Afghanistan’s complex security landscape has evolved into a sanctuary for terrorist organizations, including ISIS‑Khorasan (ISIS‑K) and Tehrik‑i‑Taliban Pakistan (TTP). U.S. Representative Bill Huizenga—Chair of the House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on South and Central Asia—warned in May 2025 that the Taliban have failed to honor their Doha Agreement pledges, allowing terrorist groups to expand within Afghanistan and even plot operations abroad【Azizi, 2025】. Simultaneously, Pakistan has launched cross‑border airstrikes targeting TTP hideouts inside Afghan territory, killing militants but also causing civilian casualties and inflaming tensions (【Reuters, 2024】【AP, 2024】). These interlinked developments are fueling a dangerous cycle of escalation, posing grave threats to regional security, undermining international counter‑terrorism efforts, and straining diplomatic stability. This report provides a detailed, sourced assessment of the situation through a complex systems lens, offering policy recommendations tailored for the U.S., NATO allies, and other global stakeholders.

2. Background

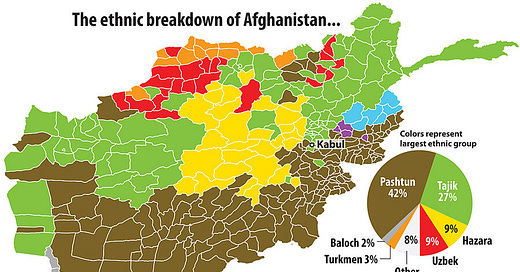

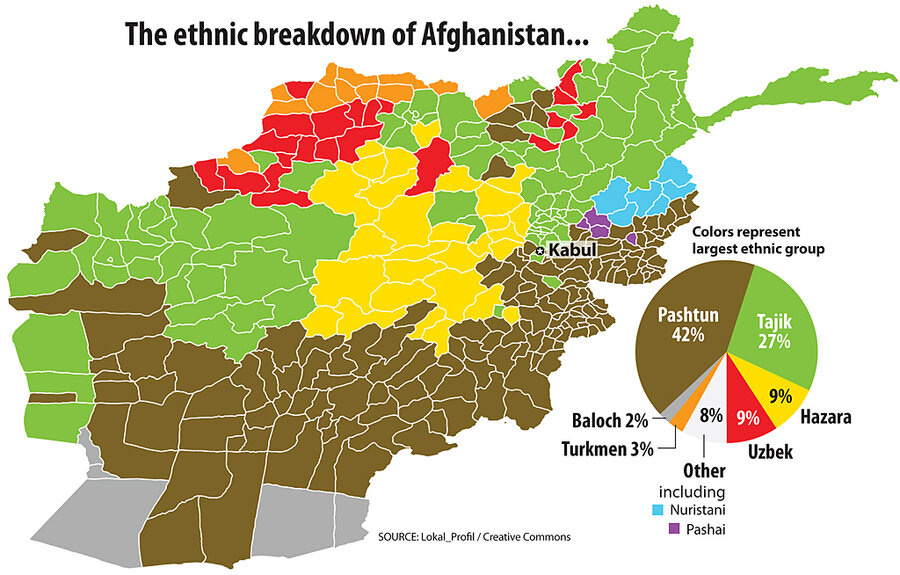

The Taliban’s return to power in August 2021—culminating in the Doha Agreement—included a pledge to prevent Afghanistan from becoming a terrorist haven【Azizi, 2025】. However, the aftermath of the U.S. withdrawal saw a resurgence of militant networks, which exploited the power vacuum. The Islamic State’s Khorasan branch (ISIS‑K) rebounded after 2021, while the Pakistani Taliban (TTP) found increased freedom of movement along the Afghan–Pakistan frontier. Pakistan historically maintained tacit ties with the Afghan Taliban (facilitated by its intelligence services) and tolerated the TTP's presence in the Afghan border regions. Those dynamics shifted as TTP-led violence surged, including unprecedented waves of suicide bombings and ambushes against Pakistani security forces in 2022–2023【Reuters, 2024】【Stein, 2025】. Islamabad’s patience has frayed, perceiving the Afghan Taliban as either unwilling or unable to crack down on TTP sanctuaries. Notably, sectarian and ethnic fissures also persist within Afghanistan: for example, the Shi’a Hazara communities of central Afghanistan (long persecuted by Sunni extremist groups) remain distrustful of Taliban rule. ISIS‑K has cynically exploited these divides by targeting Hazara Shia mosques and gatherings in deadly attacks, further entrenching the country’s role as a breeding ground for sectarian terrorism. In summary, Afghanistan’s internal fragilities and regional entanglements set the stage for the post-withdrawal scenario of a haven.

3. Key Developments

U.S. Congressional Warning:

On May 22, 2025, Rep. Huizenga emphasized in a subcommittee hearing that despite the Taliban’s Doha commitments, Afghanistan has “once again become a hotbed for terrorists looking for safe harbor” as groups like ISIS‑K and TTP reach historic threat levels【Azizi, 2025】. He cautioned that extremists on Afghan soil are rapidly growing their ranks and capabilities to project attacks internationally, underscoring the failure of the Taliban to uphold counter-terror promises.

Airstrikes by Pakistan:

On 24–25 December 2024, Pakistan conducted coordinated airstrikes on suspected TTP training camps in Afghanistan’s Paktika province. Dozens of Pakistani Taliban militants were killed in the strikes【Reuters, 2024】. However, Afghan officials reported that the bombardment also caused significant collateral damage, with as many as 46 people killed, including women and children, according to Taliban claims【AP, 2024】【Al Jazeera, 2024】. These strikes marked a significant escalation as Islamabad directly targeted militants across the Durand Line, reflecting Pakistan’s growing resolve to eliminate TTP safe havens despite the risks of Afghan civilian casualties.

Taliban Retaliation Threats:

In response to the December air incursions, Taliban forces carried out reprisal attacks across the border in late December 2024. Taliban units targeted several points inside Pakistan (reportedly border security outposts and infrastructure) as a form of retaliation【Reuters, 2024】. The Taliban government also issued stern warnings to Islamabad, condemning the violation of Afghan sovereignty and vowing consequences for any future Pakistani military actions inside Afghanistan. This exchange of strikes and threats demonstrated a rapid deterioration in Afghanistan–Pakistan relations following the TTP-focused operation.

Escalated Border Clashes:

The tit-for-tat military actions soon expanded into broader border clashes. Open-source casualty reports indicate that over 900 combined fatalities (military and civilian) occurred during the intensified Afghanistan–Pakistan border skirmishes of late 2024【Wikipedia, 2024】. Frontier districts saw firefights, artillery shelling, and mass displacement of villagers. The sheer scale of losses underscored how quickly a counter-terror operation spiraled into a wider armed confrontation, raising alarms about a potential conventional conflict between the two countries.

4. Analysis of Impact

4.1 Global Socio‑Economic Effects:

Afghanistan’s re-emergence as a terrorist haven has dampened foreign investment and complicated the delivery of humanitarian aid. Fear of terror attacks and chronic instability deters international businesses and NGOs, worsening Afghanistan’s economic isolation. In neighboring Pakistan, the security fallout has disrupted cross-border trade and transit routes. Pakistan’s punitive military responses and persistent TTP insurgency are impeding major economic initiatives. Trade corridors integral to the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor and broader Belt & Road infrastructure projects face heightened risk and uncertainty (Stein, 2025). As a result, regional economic integration and development suffer, illustrating how violence in one node of this complex system cascades into socio-economic consequences across South and Central Asia.

4.2 Socio‑Political Implications:

The Taliban’s inability (or unwillingness) to suppress extremist factions on Afghan soil is eroding their legitimacy at home and abroad. Internally, high-profile attacks by ISIS‑K on civilians (predominantly minority Shi’a) and unchecked TTP activity make the Taliban appear weak in enforcing security, undermining their claim of bringing stability after decades of war. This emboldens local dissent and could potentially spur pockets of resistance (e.g. in non-Pashtun regions) to coalesce in the future. Regionally, Islamabad’s strategic pivot in dealing with Kabul highlights growing frustration. In May 2025, Pakistan announced it would finally send an ambassador to the Taliban’s Afghanistan, upgrading diplomatic ties for the first time since 2021 (Reuters, 2025). This move signals that Pakistan, despite its anger, prefers to engage the Taliban regime formally – both to press its counter-terror demands and to explore alternate partners (like China or Gulf states) to influence Kabul. Other neighbors, such as the Central Asian republics and Iran, also view the Taliban’s faltering counter-terror performance as a political liability, complicating prospects for formal recognition or cooperation. Overall, the post-withdrawal reality has left the Taliban diplomatically isolated and struggling to balance competing pressures, a hallmark of the complex political ecosystem now in place.

4.3 Security Concerns and Risks:

The security vacuum in Afghanistan has enabled transnational jihadist groups to regenerate. ISIS‑K’s expanding operational reach is particularly alarming: despite Taliban crackdowns, ISIS‑K has proven capable of high-casualty attacks in Kabul and even attempts beyond Afghanistan’s borders. Its ideological feud with the Taliban adds an extra layer of violence, as ISIS‑K seeks to discredit Taliban authority by attacking vulnerable targets (including ethnic/religious minorities and foreign interests). Meanwhile, the TTP’s entrenched presence in eastern and southern Afghanistan poses an existential threat to Pakistan’s security, evidenced by the surge in cross-border raids and suicide bombings originating from Afghan sanctuaries【Reuters, 2024】. The interplay of these actors is inherently complex: the Taliban have selectively fought ISIS‑K (due to a direct threat to their rule) but largely tolerated or even covertly supported TTP fighters, given ideological kinship and historical ties. This dual approach undermines a unified counter-terrorism strategy. It frustrates U.S. and allied efforts to deny terrorists any haven, as Western intelligence agencies lack on-the-ground partners willing to target all extremist groups equally. The net result is a patchwork of security risks radiating outward – from the immediate threat of mass-casualty terror strikes, to the long-term danger of Afghanistan once again hosting globally-oriented terrorist training camps. Without coordinated intervention, Afghanistan’s soil could incubate the following central international terror plot, making the situation a top-tier global security concern.

4.4 Peace and Stability Considerations:

The ongoing escalations between Pakistan and the Taliban regime threaten to ignite a broader conflict that could shatter the relative calm Afghanistan saw immediately after 2021. Each border provocation and retaliation increases the likelihood of miscalculation. The feedback loop of violence – Pakistani airstrikes prompting Taliban reprisals, which in turn provoke further Pakistani response – exemplifies how quickly instability can spiral in a complex adaptive conflict system. Diplomatic channels between Kabul and Islamabad are badly strained; trust is virtually nonexistent. Efforts by China, the U.S., or other powers to mediate have so far had limited impact on tempering either side’s military impulses. If these tit‑for‑tat exchanges continue unchecked, they could escalate into a conventional interstate clash, a scenario not seen in this region in decades. Such an outcome would not only devastate border communities but also set back any peace process for Afghanistan and destabilize the wider region. The current trajectory demonstrates an alarming lack of strategic restraint (Azizi, 2025) among the involved actors. Without intervention, the equilibrium of deterrence may fail, making peace increasingly elusive. A more coordinated strategy is required to break this cycle and restore stability, or else Afghanistan and its neighbors face a highly uncertain and perilous future.

5. Implications for Stakeholders

5.1 United States – Strategic Reorientation Required

Intelligence: Increase focus on human intelligence (HUMINT) and technical surveillance targeting ISIS‑K and TTP networks in Afghanistan. The U.S. should rebuild an intelligence architecture for Afghanistan from afar – leveraging regional partners, drones, and informants – to monitor terror training camps and leadership movements. Real-time intel sharing with Pakistan will be crucial to enable pre-emptive actions against imminent threats.

Diplomacy: Consider re-engaging with the Taliban regime through back-channel or conditional dialogues focused strictly on counter-terrorism. While the U.S. and its allies do not officially recognize the Taliban government, pragmatic engagement (e.g., in Doha or via intermediaries like Qatar) could pressure Taliban leaders to rein in groups like TTP and Al-Qaeda. The U.S. can also rally international consensus (at the UN Security Council and beyond) to hold the Taliban accountable to its Doha Agreement commitments regarding terrorism.

Military: Prepare for “over-the-horizon” contingency operations. The U.S. may need to conduct limited kinetic strikes (with drones or special operations forces) on high-value terrorist targets in Afghanistan if an imminent threat to U.S. or allied interests is detected. Such actions should ideally be coordinated with Pakistan to allow the use of airspace and avoid misunderstandings. Additionally, expanding security assistance and training to Pakistan’s counter-terror units can help build a bulwark just outside Afghanistan’s borders, containing the terrorist threat from spilling over.

5.2 Western Allies (NATO, EU) – Collective Vigilance and Conditional Engagement

Intelligence Sharing: NATO members and EU security services should seamlessly share any Afghanistan-related terrorism intelligence with both the United States and Pakistan. Given the distributed nature of ISIS-K’s recruitment (which now spans multiple countries) and TTP’s potential to target beyond Pakistan, a multilateral intelligence fusion is needed to map and disrupt networks before attacks occur. Joint analytic cells or task forces could be established to pool resources.

Leverage on Aid: Humanitarian and developmental aid to Afghanistan should be explicitly tied to the Taliban’s counter-terror performance. European donors and international financial institutions must adopt rigorous conditionality – for example, releasing funds for healthcare or food aid only upon evidence that the Taliban are actively constraining terrorist operations. To ensure aid still reaches Afghans in need, channels can bypass the Taliban government (using NGOs or UN agencies) while making clear that large-scale assistance or any pathway to diplomatic recognition hinges on tangible counter-terror actions by the regime.

5.3 Major Global Actors – Stakeholder Roles in the Regional System

China: Beijing is likely to deepen its engagement with Afghanistan, driven by interests in regional stability and mineral resources. China may expand infrastructure investments (e.g., extending CPEC into Afghanistan) and security cooperation with the Taliban to safeguard its projects and personnel. However, China must weigh these opportunities against the security risks, including the presence of Uyghur militant groups in Afghanistan that threaten Chinese interests. Beijing could leverage its influence in Islamabad and Kabul to facilitate dialogue, positioning itself as a mediator to manage tensions between the TTP and the Taliban.

Russia & Iran: Both Moscow and Tehran are concerned about ISIS‑K’s growth, given the group’s virulent anti-Shia stance and potential to infiltrate Central Asia or Iran’s eastern border. They will likely seek to coordinate intelligence with the Taliban (and possibly with each other) to track ISIS‑K cells. Russia, facing its issues with jihadists from Central Asia, might increase support to counter-terrorism efforts in Afghanistan through the Moscow-led regional formats. Iran, sharing a long border with Afghanistan and protecting the Hazara Shia population, might engage the Taliban with a mix of pressure and limited security cooperation to curb Sunni extremist threats.

India: New Delhi has to navigate its role carefully. India has economic and strategic interests in Afghanistan (such as infrastructure projects and using Iran’s Chabahar port to access Afghan markets). Yet, it remains wary of a Taliban-Pakistan-China nexus forming. India will likely maintain a low-profile engagement, offering humanitarian aid and retaining ties with former Afghan republic figures, while closely observing Taliban toleration of anti-India terror groups like Jaish-e-Mohammed or Lashkar-e-Taiba. Any sign of Afghanistan being used as a staging ground for Kashmir-centric militancy could provoke a strong response from India. Thus, India’s investments in Afghanistan’s stability will be calibrated against its rivalry with Pakistan and the security of the subcontinent.

5.4 Multilateral Institutions – Facilitating Coordination and Accountability

United Nations / OSCE: The UN should consider deploying special border monitoring missions or, at the very least, enhancing the UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) with a mandate to track cross-border militant movements and human rights impacts. An investigative panel under UN auspices could document the December 2024 strikes and subsequent clashes, providing an impartial account and keeping civilian protection on the international agenda. Periodic UN Security Council briefings on Afghanistan should specifically address the status of terrorist safe havens and Taliban compliance with Resolution 2593 (which demands that Afghan soil not be used by terrorist groups).

Regional Coalitions: Existing forums, such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) or ad-hoc trilaterals, should be leveraged to defuse the crisis. For instance, China could convene a tripartite security dialogue among Pakistan, the Taliban administration, and Chinese officials. The focus would be on establishing protocols for border security and intelligence sharing to manage threats like TTP and ISIS-K jointly. Such a dialogue, perhaps expanded to include Russia or Central Asian states, can help institutionalize communication and reduce the chance of misunderstandings leading to conflict. Regional bodies like the OIC (Organization of Islamic Cooperation) could also press the Taliban on theological grounds to cease sheltering militants who endanger Muslim nations like Pakistan.

6. Recommendations

Structured U.S.–Pakistan Intelligence Initiative: Launch a joint intelligence task force between American and Pakistani agencies dedicated to Afghanistan-focused terrorism threats. By combining U.S. technological capabilities (signals intelligence, satellite imagery) with Pakistan’s human intelligence and local knowledge, such a platform can map militant networks in near real-time. Regular intelligence exchanges and coordinated operational planning will build trust and enhance both countries’ ability to preempt attacks. This initiative should also involve periodic trilateral briefings with Afghan Taliban representatives to share actionable data on ISIS‑K and Al-Qaeda, testing the Taliban’s willingness to cooperate against those groups.

Taliban–Regional Security Dialogue: Create a formal security dialogue bringing Taliban officials together with key regional stakeholders (Pakistan, China, Russia, Iran, and Central Asian neighbors). Hosted by a neutral party (for example, Qatar or the UN), this forum would set expectations and verification mechanisms for counter-terror commitments. Agenda items could include establishing joint border security commissions, Taliban pledges to expel or hand over foreign terrorists, and frameworks for cross-border hot pursuit or strikes (to avoid unilateral actions). While challenging, direct engagement in a multilateral setting may pressure the Taliban to respond to collective concerns and reduce miscalculations, such as those seen in late 2024.

Aid Tied to Counter-Terror Metrics: International donors, led by the U.S. and the EU, should develop a unified system of benchmarks to evaluate the Taliban’s counter-terrorism performance. For example, metrics might include the number of terror suspects arrested or expelled by the Taliban, evidence of closing terrorist training facilities, and the frequency of attacks emanating from Afghan soil. Future financial aid and development support must be explicitly contingent on meeting these benchmarks. A jointly administered trust fund could hold aid in escrow and disburse it in tranches when independent monitors confirm progress. This approach would incentivize the Taliban to take concrete action against groups like TTP, while providing a face-saving way for them to claim rewards for compliance.

Bolster Civil Society Programming: To address the long-term roots of extremism, invest in community-level counter-radicalization in Afghanistan and Pakistan’s border regions. Programs could include funding local radio, social media campaigns, and schools (particularly in Pashto and Dari languages) that promote moderate interpretations of Islam and expose the falsehood of extremist propaganda. Engaging respected religious scholars and tribal elders in these efforts is key to credibility. Additionally, expand vocational training and job creation projects for youth in vulnerable areas, reducing the lure of militant recruitment by offering alternative livelihoods and a sense of inclusion. These initiatives require careful oversight to ensure the Taliban do not co-opt or suppress them, possibly executed through NGOs with quiet backing from international donors.

Surveillance and Early-Warning Platforms: Leverage technology to establish an early warning system for cross-border militant incursions and terrorist plots. This could involve deploying advanced surveillance drones along the Durand Line and sharing live feeds with both Afghan and Pakistani authorities. The U.S. and NATO allies can assist with satellite imagery analysis to detect new militant camps or suspicious movements in remote Afghan provinces. Furthermore, enhance social media and communications monitoring (with due regard for privacy) to pick up chatter indicating planned attacks. By pooling these intelligence resources in a joint coordination center (potentially hosted in a third country, such as Qatar or the UAE), stakeholders can gain a more predictive view of the threat landscape and act before incidents escalate.

7. References

Al Jazeera. (2024, December 25). Pakistan air strikes in Afghanistan spark Taliban warning of retaliation. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/12/25/pakistan-air-strikes-in-afghanistan-spark-taliban-warning-of-retaliation

AP. (2024, December 24). Airstrikes target suspected Pakistani Taliban hideouts in Afghanistan. Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/aac6f1f0aa42f1f3ad88f619b7305724

AP. (2024, December 25). Taliban say Pakistani airstrikes killed 46 people in eastern Afghanistan, mostly women and children. Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/1eb6ebd92403795d03856b1b97cac0da

Azizi, A. (2025, June 27). US lawmaker says Afghanistan has again become ‘hotbed for terrorists’. Amu TV. https://amu.tv/182927/

Reuters. (2024, December 25). Pakistani airstrikes on Afghanistan kill 46 people, Taliban official says. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/least-46-killed-pakistani-bombardment-afghanistan-afghan-taliban-spokesperson-2024-12-25/

Reuters. (2024, December 28). Afghan Taliban forces target ‘several points’ in Pakistan in retaliation for airstrikes. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/afghan-taliban-forces-target-several-points-pakistan-retaliation-airstrikes-2024-12-28/

Reuters. (2025, May 30). Pakistan announces it will send an ambassador to Afghanistan to upgrade diplomatic ties. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/pakistan-announces-it-will-send-ambassador-afghanistan-upgrade-diplomatic-ties-2025-05-30/

Stein, M. (2025, April 3). Pakistan’s counterterrorism efforts could ignite wider conflict in the region. Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO). https://fmso.tradoc.army.mil/2025/pakistans-counterterrorism-efforts-could-ignite-wider-conflict-in-the-region/

Mills, P. (2022, November 29). Mapping Anti-Taliban Insurgencies in Afghanistan. Institute for the Study of War & Critical Threats Project. https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/mapping-anti-taliban-insurgencies-afghanistan

Wikipedia. (2024). 2024 Pakistani airstrikes in Afghanistan – Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. (accessed June 27, 2025). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2024_Pakistani_airstrikes_in_Afghanistan

Wikipedia. (2024). Afghanistan–Pakistan clashes (2024–present) – Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. (accessed June 27, 2025). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Afghanistan–Pakistan_clashes_(2024–present)

Wikipedia. (2025). Afghanistan–Pakistan relations – Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. (accessed June 27, 2025). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Afghanistan–Pakistan_relations

8. Disclaimer

This report is a confidential analytical product based entirely on open-source information. All data was current as of June 27, 2025. The findings and conclusions drawn here are the author’s own and do not represent any official position of any government or agency. This document is intended for intelligence assessment purposes only; it is provided “as is” without warranty of accuracy or completeness. Use of this analysis should be accompanied by appropriate caution, given the fluid situation on the ground.

9. Analyst Identification

Prepared by Ronald J. Botelho, MS

Distribution: Open Source (Permitted to share under license terms)

10. License

MIT License – Permissive use allowed with attribution.